The Singapore Registry of Ships (SRS) has continued to perform well under Port State Control (PSC) in the first three quarters of this year due to the collective efforts of our stakeholders and seafarers.

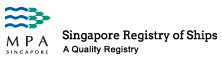

Under the Tokyo MOU Regime, SRS’ detention ratio in 2014 was 0.95% against the regime’s average of 4.09%. The slight increase in detention ratio over 2013’s detention ratio was due to an increase in the number of detentions in Australia. The continuous improvement has led to SRS’ lowest 3-year rolling average detention ratio of 1.06% this year.

Tokyo MOU Detention Ratio

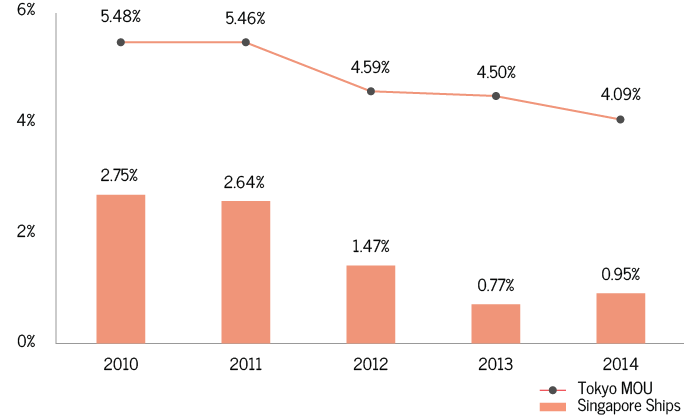

Tokyo MOU 3-Year Rolling Average Detention Ratio

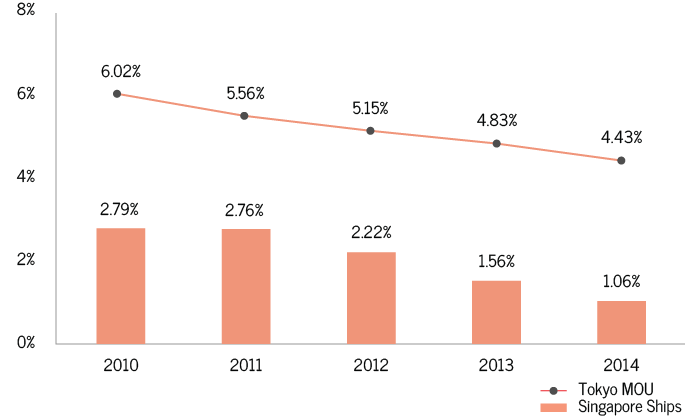

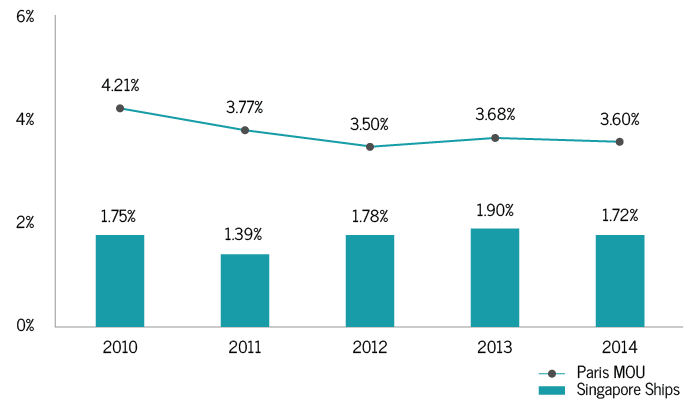

Under the Paris MOU Regime, SRS’ detention ratio in 2014 was 1.22% against the regime’s average of 3.30%. Our 3-year rolling average in 2014 was 1.72% against the regime’s average of 3.60%. Both ratios are an improvement over the past two years.

Paris MOU Detention Ratio

Paris MOU 3-Year Rolling Average Detention Ratio

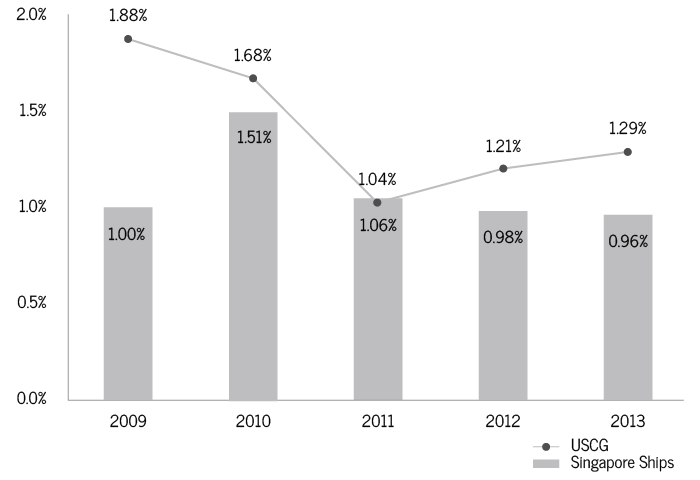

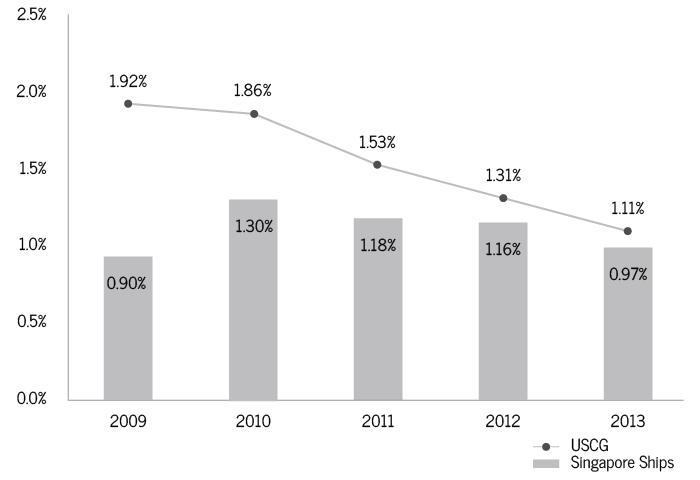

Under the USCG, SRS’ detention ratio in 2013 was 0.96% against the regime’s average of 1.29%. Our 3-year rolling average in 2013 is 0.97% against the regime’s average of 1.11%. This also means that SRS qualifies again for the US Coast Guard’s QUALSHIP 21 programme this year after a three year wait.

USCG Detention Ratio

USCG 3-Year Rolling Average Detention Ratio

Under FSC, our detention ratio in 2014 is 1.34%, which is the lowest in the last five years.

Marine Surveyor Inspection Applications

MPA Flag State Control surveyors will soon be provided with mobile devices and inspection applications to enable them to conduct ship inspections more efficiently.

Currently, MPA surveyors spend a significant amount of time in administrative work, using various databases in the office to identify and select ships in port for inspection, and gathering relevant information about the ships before they head out to the field. Due to the lack of updated information, surveyors might miss the ship if it leaves port earlier than expected. As part of their job, surveyors will have to issue the hard copy inspection report to ship’s masters, and subsequently upload the report into the inspection database before filing the report.

In order to conduct ship inspections in a smarter and more efficient way, MPA has developed a mobile device and inspection applications to provide the surveyors with a single mobile platform to quickly size up and shortlist ships in port for inspections. They will also have access to real time information on the movement of ships in Singapore waters as well as the means to check on technical and regulatory information anytime and anywhere.

With the inspection application, MPA surveyors can easily prepare and issue their inspection reports electronically and snap photos of ships as objective evidence for their inspection reports. They can also submit their inspection reports directly to the office database while on the move. As part of safety measure, surveyors can report to the office using the app when they have embarked on and disembarked from the ship. The project was awarded the Ministry of Transport Minister’s Innovation Award (Merit) in 2014.

Seafarers’ Rest Hours Comes under Scrutiny

All ships are required to be sufficiently and efficiently manned to ensure safe operations at all times, and to comply with the relevant requirements of SOLAS, STCW and the Maritime Labour Conventions for seafarers’ hours of rest and watch-keeping. This is to prevent the ship’s crew from being affected by fatigue, which has been widely recognised as a common contributing factor of serious marine accidents and casualties.

From 1 September to 30 November 2014, Member Authorities of the Paris and Tokyo Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on Port State Control (PSC) will be conducting a joint Concentrated Inspection Campaign (CIC) to enforce the requirements of the STCW Manila Amendments on seafarers’ hours of rest.

FATIGUE impairs human performance!

Inability to concentrate

Diminished decision-making ability

Poor memory

Slow down in physical and mental reflexes

Change in mood

Change in attitude

Loss of control of bodily movements

During PSC inspections, ships will be checked for strict compliance with the requirements of SOLAS regulation V/14 and Chapter VIII of the STCW Convention and Code as follows:

The ship shall be manned in accordance with the Minimum Safe Manning Document.

All watch-keeping officers and ratings, and seafarers designated with safety, pollution prevention and security duties shall be provided with a rest period of not less than:

a minimum of 10 hours of rest in any 24-hour period; and

77 hours in any 7-day period.

Rest hours may be divided into no more than 2 periods, one of which shall be at least 6 hours in length, and intervals between consecutive periods of rest shall not exceed 14 hours.

-

Watch schedules or tables of shipboard working arrangements shall be posted where they are easily accessible, in a standardised (IMO/ILO) format, in working language(s) of the ship, and also in English.

-

Seafarers who are on call shall have adequate compensatory rest periods if their normal rest period is disturbed by call-outs to work.

All watch-keepers shall be sufficiently rested for the first and subsequent watch at the commencement of the voyage.

-

Records of seafarers’ hours of rest shall be correctly maintained on a daily basis in a standardised format, in working language(s) of the ship and also in English, to allow monitoring and verification of compliance with mandatory requirements.

-

Seafarers shall receive a copy of their rest hour records, which shall be endorsed by the master or by a person authorised by the master and also by the seafarers themselves.

Records on board shall indicate that a bridge lookout is being maintained, in particular during hours of darkness.

A ship may be detained if it does not comply with minimum safe manning requirements, if rest hours records on board are falsified, or if any watch-keeper is not sufficiently rested on the first and subsequent watch at the commencement of the voyage.

Common deficiencies

The following deficiencies have often led to ships being detained and subject to additional ISM audits when there is deemed to be evidence of a serious failure of the company’s or shipboard’s Safety Management System:

-

Records of rest hours were not being maintained on a daily basis by individual seafarers.

-

Records of rest hours of individual seafarers were falsified or did not reflect actual hours of rest or work on board the ship.

Hours of rest of watch-keeping personnel did not comply with the minimum STCW or MLC requirements.

-

Table of shipboard working arrangements did not reflect actual working arrangements on board the ship.

-

The shipboard Safety Management System failed to ensure that watch-keeping personnel are adequately rested, or that records of seafarers’ hours of rest are factually and accurately maintained on board.

The underlying reasons for the above deficiencies are many. The following have been identified during investigation:

-

The company has not established adequate policy guidance, procedure or instructions to ensure mandatory rest hour requirements are properly monitored and verified for compliance.

-

The master and crew were not aware of or did not understand the purpose of complying with the STCW or MLC requirements and how it may help prevent fatigue. If they do, they may view the recording and monitoring of rest periods on their ships as an administrative burden and treat it as a “paper exercise”. If records of rest being kept by individual seafarers are not factual, they will invariably contradict the operational records in the ship’s deck and engine log books or bell books.

-

Tables of shipboard working arrangements were not properly established to allow seafarers to know their anticipated or routine daily work and rest periods at sea and in port such that additional hours of work can be easily monitored and dealt with as required to ensure compliance with minimum rest periods.

Additional hours of work during arrival and departure passages and during port stays which affected the seafarer’s minimum rest periods were not being monitored and compensated to correct any non-compliance.

-

In many instances, there was no process or procedure in place to ensure that the accuracy of the records of rest hours kept by individual seafarer and compliance with minimum rest periods for every 24-hour and 7-day period were being verified by the master or the persons authorised by the master, before they endorsed the records.

To avoid similar problems, companies could leverage on their safety management system to ensure compliance with seafarers’ rest hour requirements and prevent fatigue on their ships. They could review their current working arrangements in their company and onboard their ships, and implement necessary policies, procedures, control measures, training and shipboard familiarisation to address the safety deficiencies that are listed above.

References:

Resolution A.1047(27) - Principles of Minimum Safe Manning

IMO/ILO Guidelines for the Development of Tables of Seafarers’ Shipboard Working Arrangements and Formats of Records of Seafarers Hours of Work and Rest)

MSC/Circ.1014 - Guidance on Fatigue Mitigation and Management