| Case study 1 – Illegal discharge of Engine Room bilge waters – in US waters |

|

What happened Whilst the vessel was berthed at a container terminal, the Second Engineer deliberately discharged oily water from the Engine Room bilge well through the Fire, Bilge, Ballast pump by cracking open the sealed bilge suction valves, bypassing the Oily Water Separator (OWS). The port authorities initiated an emergency response to contain the pollutant. The vessel was subsequently detained, and upon completion of investigations, a lawsuit was served against the Company, the vessel, and its crew. The Chief Engineer and the Second Engineer pleaded guilty to the charges, and each were given probation and prohibition from serving onboard any commercial vessels trading the United States during their terms of probation. The Company pleaded guilty to –

- for which the Company was ordered to pay a criminal penalty of US$3 million, and to serve a four-year probation, during which time, all vessels operated by the Company which call at ports in the United States will be required to implement a robust Environmental Compliance Plan. How and Why, it happened The Second Engineer, when taking over the Engine Room watch at 0800AM, noticed that the Engine Room bilge wells were at high level, almost reaching the tank-top, due to an overflow from the Boiler Cascade Tank. Assuming that the water from the Boiler Cascade Tank was clean water, the Second Engineer then decided to reduce the content level of the bilge wells. Although he knew that the act was unsafe and prohibited, the Second Engineer opened the starboard bilge well suction valve to discharge the contents of the bilge wells overboard.

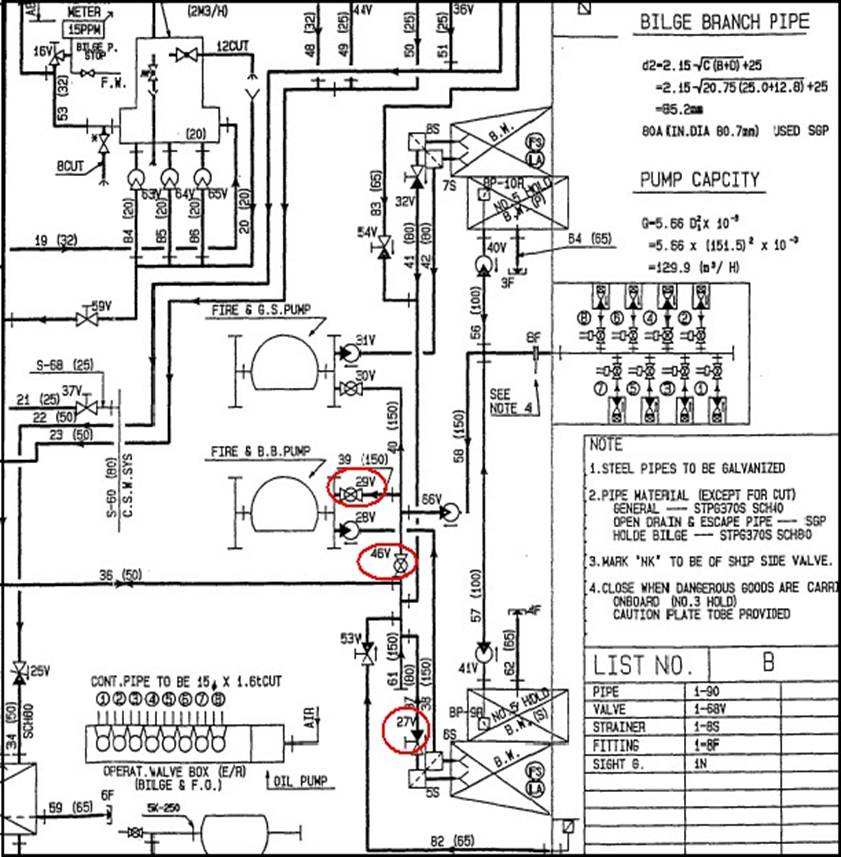

#1 – Improper sealing. Valves can be cracked open.

#2 – The Bilge Piping System from the Bilge Well to the Fire, Bilge and Ballast Pump The Engine Room bilge wells were full with water because of the following events –

|

| Case study 2 – Illegal discharge of bilge waters using ‘magic pipe’ – Off Myanmar |

|

What happened A Second Officer, acting on information provided by a concerned Engine Room Rating, notified his Company’s Superintendent through photographs showing an illegal discharge carried out overboard. The Company then conducted a shipboard investigation into the whistle-blowing incident. The Company’s investigation revealed that the engineers, under the instruction of the Chief Engineer, had used a “magic pipe” and “flexible hose” to discharge waters from the Engine Room bilge tank directly to the sea, bypassing the OWS. A connection – “the magic pipe” - was fabricated to discharge the said-waters through the flange of the pressure gauge of the ballast water stripping eductor line. #1 – use of “flexible hose” and “magic pipe” from sounding pipe of Bilge Tank to the eductor system How and Why, it happened The reason for bypassing the OWS and discharging directly overboard were –

|

| Case study 3 – Garbage disposal in Great Barrier Reef, Australia |

|

What happened During an AMSA inspection at Brisbane, Australia, the Singapore-registered vessel received four deficiencies including one detainable deficiency (code 30) which are related to the discharge of food waste inside Australia’s “NO MARPOL discharge areas”. The deficiencies in question are –

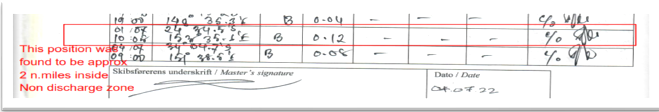

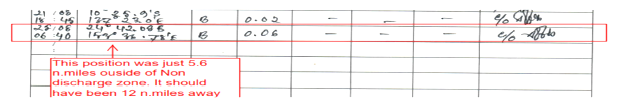

How and Why, it happened AMSA officers had found that entries in the Ship’s Garbage Logbook showed that the vessel had discharged non-comminuted food wastes within the “NO MARPOL discharge areas” on two separate occasions.

#1 – On 1st July 2022, the vessel discharged food wastes in position 24° 34.5’ S/ 153° 35.6’ E, which lies within 2 nm of the nearest land line of the NE coordinates of Australia.

#1 – On 25th August 2022, the vessel discharged food wastes in position 24° 42.08’ S/ 153° 36.78’ E, which lies within 5.6 nm of the nearest land line of the NE coordinates of Australia. Due to the lapse on the part of the officer planning the passage which was overlooked by the Master and the Chief Officer, specific information about the extent of the “no discharge area” was not clearly displayed on the navigation charts used. This had led to the Chief Officer to approve the discharge at these prohibited areas on the above-mentioned dates. #1 – Vessel’s crew misinterpretation and erroneous understanding of the term “nearest land line” In addition to the inadequate instructions in the Company’s procedures, the Shipboard Internal procedure also did not clearly mention the 12nm requirement from the nearest land line, beyond which the non-comminuted food wastes could be discharged. There were no specific instructions by the Master or Chief officer on the special restrictions on the vessel’s voyage route regarding garbage disposal. The Officer(s) on watch exhibited inadequate understanding of MARPOL Annex V, Regulations of discharging food wastes 12 nm away from the Nearest Land line in the Great Barrier Reef region, and on one of the occasions, the Officer was engaged in cargo planning and had misjudged the distance from land. The Deficiencies provided objective evidence that there is a serious failure of implementation of ISMC/S7 element 7 and procedures onboard for ensuring protection of the marine environment from garbage pollution. |