The Singapore Flag’s Performance in the First Half of 2016

In the first half of 2016, Singapore ships performed well under Port State Control (PSC) in both the Tokyo and Paris MoU regimes.

- Tokyo MoU regime – the detention ratio of Singapore ships is 0.88% against the regime’s average of 3.63%.

- Paris MoU regime – the detention ratio of Singapore ships is 0.96% against the regime’s average of 3.42%.

The SRS performances under the Tokyo and Paris MoU regimes over the past five years are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2 below.

Tokyo MoU - Annual Detention Ratio

Figure 1

Paris MoU - Annual Detention Ratio

Figure 2

For the first half of 2016, a total of 20 Singapore ships were detained under PSC worldwide. Of which, 56% took place in Australia (8 detentions) and the United States (4 detentions).

The breakdown of Singapore ship detentions by Port States is given in Figure 3 below.

PSC Detention of Singapore Ships by Port State in First Half of 2016

Figure 3

Most Common Causes of Ship Detentions

From the analysis of Singapore ship detentions in the first half of 2016, the four most common categories of PSC detention deficiencies are Fire Safety, Documentation & Certification, Life Saving Appliances and Emergency Systems. These categories make up 58% of the total detention deficiencies. The PSC detention deficiencies under these four categories are summarised as follows:

Fire Safety

- Ship’s crews not able to carry out satisfactory fire drills

- Use of non-approved pumping arrangement to transfer leaked cargo oil in pump-room to slop tank

- Defective fire detection and alarm system

- Defective quick closing valve for the emergency generator’s fuel oil tank

- Defective funnel damper

Documentation & Certification

- Expired interim Maritime Labour Certificate

- Expired Seafarers' Employment Agreement (SEA)

- Errors in IOPP Certificate and Supplement Form B

- Oil Record Book - Part II (Cargo/Ballast operations) not sighted on board

- Record of lowering and manoeuvring the rescue boat in water not sighted on board

- Use of unqualified engine room watchkeeping personnel during sea passage

Life Saving Appliances

- Lifeboat and rescue boat engines unable to start

- Defective lifeboat and rescue boat launching arrangement

- Hull damage on lifeboat

Emergency Systems

- Defective emergency generator

- Emergency fire pump unable to pressurise fire mains

- Emergency fire pump not able to operate on emergency source of power

The breakdown of all the PSC detention deficiencies found on Singapore ships in the first half of 2016 are given in Figure 4 and 5 below.

Detention Deficiencies by Category in First Half of 2016

Figure 4

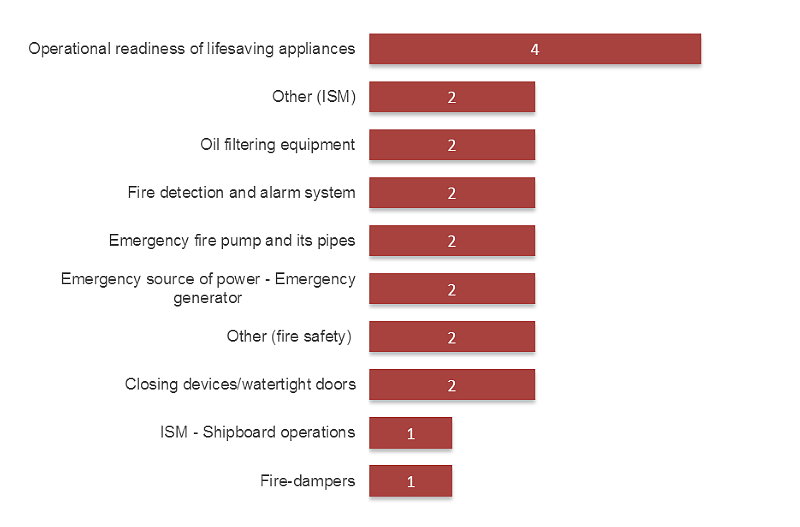

Top 10 Detention Deficiencies in First Half of 2016

Figure 5

Fire Safety On Tankers

The safety of tankers have significantly improved over the years because of changes to, and increasingly robust enforcement of, rules and regulations that now require better standards of design, construction, fire safety and the carriage of cargoes on such ships. The safe operation of tankers is also guided by the recommendations in the International Safety Guide for Oil Tankers and Terminals (ISGOTT).

However, rules and regulations alone cannot eliminate all risks on ships. Hence, the ISM Code requires the Company to establish and maintain their safety management system to ensure that the following objectives are met:

- Provide safe practices during ship operations and a safe working environment;

- Manage all identified risks to its ship, personnel and the environment; and

- Continuously improve safety-management skills and emergency preparedness of their crew’s shore-based personnel.

It is also important for the crew on tankers to have good safety awareness and to incorporate contingency planning in shipboard operations, so as to be able to deal with any unforeseen hazardous occurrences on their ships in a safe and efficient manner. The following case study highlights these points.

Case Study

An oil tanker called at an oil terminal to discharge its cargo of unleaded gasoline. Before arrival at the discharge port, the crew inspected and pressure tested the cargo system to ensure that it was in good order.

Shortly after commencing cargo operation at the terminal, the crew noticed a minor leak at the drain line of No.1 cargo oil pump. Another cargo oil pump was started to keep the cargo operation going while the crew worked on the leak. This incident was not reported to the port authority or the terminal representative as required under Regulation I/11(c) of the SOLAS Convention, and the agreement in the ISGOTT Ship/Shore Safety Check List respectively.

On the next day, a more serious leak was found in the separator drain pipe of No.1 cargo oil pump. The escaping gasoline quickly led to the deterioration of the atmosphere in the Cargo Pump Room. The cargo operation was stopped immediately. This time round, the terminal was informed of the incident, but the port authority was not.

Before the crew could tackle the leak, they had to remove the gasoline that had leaked into the Cargo Pump Room bilges and ventilate the space. Without consulting the terminal, the master allowed the crew to use a portable Wilden pump and plastic hoses to transfer the gasoline to the Dump Tank via a sounding pipe, as well as to a cargo tank via the drip tray under the portside cargo manifold. While this was going on, a Port State Control inspector came to inspect the ship. When he found out about the hazardous situation on board, he detained the ship on the following grounds:

- Unsafe condition in the Cargo Pump Room due to serious cargo leakage;

- Using unsafe means to transfer the cargo leakage in the Cargo Pump Room; and

- Failure to notify the port authority on the cargo leakage in the Cargo Pump Room.

The ship was required to leave the terminal as soon as possible to carry out repairs at the anchorage. The ship was also subject to an additional survey and ISM audit.

Upon completion of repairs, cleaning of the Cargo Pump Room, surveys and audits, the ship was allowed to return to the terminal to complete its cargo operations.

Defective drain pipe of No.1 cargo oil pump

Drain pipe of No.1 cargo oil pump after repairs.

Defective separator drain pipe of No.1 cargo oil pump

Separator drain pipe of No.1 cargo oil pump after repairs

Bilge suction in the Cargo Pump Room was not optimally situated, resulting in a significant amount of unpumpable in the Cargo Pump Room bilges in case of cargo leakages

Underlying Causes of Deficiencies

Simple and Actionable Corrective Actions

Getting the job done right the first time and every time!

- Review and improve the company’s procedure and ship/shore safety check list to ensure that the master and responsible officer informs and consults the terminal representative and the port authority on hazardous occurrences and on repairs and maintenance to be carried out on board a tanker at berth.

- Improve contingency planning for shipboard emergencies to provide appropriate response actions that can deal with the sudden failure of cargo system or serious cargo leakages in the Cargo Pump Room. This should include risk assessment to identify safety precautions to be taken and to ensure appropriate use of any temporary or alternative arrangements to address the hazardous situation in a safe and efficient manner.

- Improve the ship’s planned maintenance system to provide measures that prevent sudden failure of cargo piping system.

- Improve the arrangement of bilge suctions in the Cargo Pump Room to minimise unpumpable in case of cargo leakages.

- Training and familiarisation of the master and crew on mandatory reporting requirements, ISGOTT recommendations on Permit to Work System on board a tanker at terminal, and implementation of proposed corrective action plans.

References

- SOLAS Chapter I, regulation 11(c) - Reporting of defects which affect the safety of ship to the flag Administration, Recognised Organisation and appropriate authority of the port State

- ISM Code, paragraph 1.2.2 – Safety management objectives of the Company

- ISGOTT Chapter 4 - General precautions while a tanker is at a petroleum berth

- ISGOTT Appendix A - Ship/shore safety check list, guidelines and specimen letter

MPA Steps Up On Inspection of Life-raft Servicing Stations

The Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA) has been stepping up its efforts in the inspection of approved life-raft servicing stations in Singapore to ensure that the quality of their services is of high standard.

The inspections, which are conducted at least once a year for each station, are to ensure that the servicing stations maintain adequate facilities, use trained and competent service personnel and implement effective servicing procedures, taking into account the life-raft manufacturer’s servicing manuals.

During the inspection, the following will be assessed:

- Inspection, testing and servicing of critical components including the inflating mechanism

- Servicing, testing and packing of life-raft

- Life-raft manufacturer’s servicing manuals, servicing bulletins and instructions

- Demonstrable competence of service personnel

- Equipment calibration and maintenance procedures

- Use of proper replacement parts and materials

For stations servicing life-rafts carried on passenger ferries, the inspection may be carried out as the life-rafts are being serviced by them.

Inspection, testing and servicing of critical components of life-rafts

Annual floor seam test from the 10th year onwards

Gas inflation test at each 5-year interval

Servicing of operating head for inflation gas cylinders

Arrangement of painter in life-raft container

Packing of rafts

Securing painter to operating cable of inflation gas cylinders

Proper repacking of the life-raft to ensure efficient deployment of the life-raft during an emergency